For those who have never experienced it, homelessness will usually prompt images of people sleeping in parks, crouching in a line along the tunnel at Railway Square, or begging for money on George Street.

However, the majority of young people who experience homelessness do not live on the streets, but rather in temporary, unstable housing: they might crash in their friends’ homes, take up emergency accommodation in homeless shelters, or float from one public space with a couch to the next. It is in this transient, nomadic existence that homeless young people are often left by the wayside, faced with the trauma of losing the comfort and safety of one’s surroundings—by society’s standards, they are invisible and worthless.

And if the homeless move unseen, why would anyone care?

* * *

“When I say ‘homeless’, there’s a difference between being homeless and sleeping rough,” Andy, a 23-year-old university student who has experienced intermittent homelessness for five years, explains. “Quite often people think everyone who’s sleeping rough is homeless, when in fact there are people who have homes but may have abusive families or partners and are sleeping rough, and there are people who have temporary accommodation.”

“It’s that precarious state of not being registered, of not having a residence, or a proper home,” they say.

At the age of 18, Andy, a queer and trans student, found themselves homeless. They had grown increasingly apart from their parents after struggling to keep up with overbearing expectations over their gender and sexuality, and one day, their parents finally changed the locks on the front door of their home.

“It was a separation of sorts,” says Andy. “I remember thinking, ‘shit, where am I staying?’ I had a backpack, a tote bag and some clothes—three pairs of pants, a pair of undies, and the top I was wearing—nothing else.”

Andy was enrolled at university, and this allowed them access to the Queerspace (an autonomous, safe space for queer students on campus) for several nights. Looking for accommodation proved increasingly difficult and turned into a vicious cycle—they were actively denied by homeless shelters on the basis of their gender and sexuality, and then by the rental market because they were homeless.

“There’s this huge gap that exists between homeless shelters and actual housing,” they say. “They can do that because they have power over you. You are not registered with anything; you don’t have any documentation to prove yourself.”

Eventually, although a social worker helped Andy through the process of filling out paperwork, it didn’t help ease the mental transition.

“Being homeless is like everything in life is on pause. You just don’t have the emotional capacity to deal with forms because it’s not a priority,” says Andy. “The priority is where you’re sleeping for the night, if you’re warm, and if there’s any food. It’s the basic stuff.”

Currently, Andy is living in transitional housing arranged by their social worker in the Inner West.

“When I first walked into the house, the only thing I managed was to run around the house, go up to my room, fall on the bed and cry… I hadn’t cried in so long,” they reflect. “I realised that I could now deal with emotions because I can do things other than be homeless 24/7.”

For Andy, however, the trauma of being homeless hasn’t been resolved simply by finding a room with a bed. They are constantly struggling with poor mental health and depression, only worsened by the constant search for a sense of purpose in life.

“That’s the battle—when you’re homeless, you’re at risk of violence and [poor] mental health, but they think it can be solved by putting a roof over your head. They don’t realise that if you’re not followed up or supported to figure out what you’re going to do with yourself, you’ll just fall straight back into homelessness.”

* * *

The most common causes of homelessness are domestic and family violence, often affecting queer people. Other causes include financial burden, unaffordable housing, and drug and alcohol abuse.

These issues leave many young people trapped between sleeping rough and staying in temporary accommodation. For service providers and support groups, the main priority is preventing the progression to chronic homelessness.

Homelessness can have devastating effects on young people—high rates of mental health problems, substance abuse, and sexually transmitted infections, while deteriorating health can contribute to a lack of wellbeing.

In 2014, over 250,000 Australians accessed homelessness services, of which 87,774 adults received support for family or domestic violence, and 16 per cent of all clients identified a ‘housing crisis’ as the main reason for seeking assistance. And yet, in June of the same year, $29.1 million in federal funding was lost from reducing homelessness and facilitating early intervention to prevent young people becoming homeless. A submission to the Legislative Council of the NSW government on the issue stated that, “the removal of $29.1 million in Commonwealth government funding for homelessness in NSW the cuts “will have flow-on impacts to the wider housing and homelessness sectors.”

Within the City of Sydney, homelessness has been steadily rising over the years. A street count conducted by the City Council in February earlier this year estimated that there are over 800 homeless people—an increase by 26 per cent in the past year—with 365 sleeping rough or staying in overnight shelters, and 462 in occupied hostel beds.

However, when it comes to discussing how to best end long-term homelessness, the answers remain short. Perhaps rather aptly, the City of Sydney website states: “Homelessness is a complex issue with no single solution”.

* * *

Mark, a fourth year Engineering student, became homeless at age 16 following his escape from a controlling, abusive family environment. The situation spiralled out of control after his mother chased him out of the house with a pair of scissors. Suddenly he was running for his life, and after wandering for a few hours, he went to his local library and searched “youth homeless shelters”.

“I got in touch with Caretakers Cottage in Bondi and they started their case management—I got interviewed by some counsellors, and coupled with the DOCS record of my family from incidents involving my older autistic brother, it was determined my home life was dangerous,” he says.

The service helped Mark to apply for Centrelink payments, and lined him up with a medium-term share house. “I snuck home a few times while my mum was at work to collect my clothes, laptop and other belongings. I continued going to work, surf club and other things. When school came back, I kept going, except now every teacher knew I was living independently,” he explains.

After finishing his HSC, Mark applied for university and lived just as he was before, except he was no longer “getting yelled at or beaten every other day”. His caseworker informed him that starting university meant leaving the share house due to high demand for medium-term accommodation, and Mark moved into on-campus housing.

But homelessness has helped shape Mark’s understanding of the issue through the people he’s met along the way. “The stereotype of homeless youth is a poor kid with alcoholic parents or drug issues and a broken family. My caseworker once said they exist, but are in the minority and rarely ask for help. Some don’t make it and end up on the street,” he says.

“The other kids I met in the program had some pretty horrible stories—gay, bi and trans kids by the dozen who came out to their parents and then got shown the door or faced such abuse they had to leave,” says Mark. “These kids thought they had loving parents who wouldn’t care about their sexuality and suddenly, ‘nope, out you get’. A few kids were homeless because an accident or illness killed their parents, and they had nowhere else to go.”

Luckily for Mark, support came from day one, which has helped him to plan things effectively. His advice to young people facing homelessness is to seek support and start planning almost immediately. “If you have a job, start saving. If you don’t, keep trying to find one. Learn how to cook a few meals, how to do washing and ironing, and other life skills. Shit happens, and then your current support is gone,” he says, matter-of-factly.

* * *

The Step Ahead research conducted by Professor Marty in 2010 highlighted that “the pathway through university for young people affected by homelessness is achievable, but fraught”.

University students who are homeless can often fall between the service categories of adult and youth homelessness. As such, there is little research on university students who have been homeless, with no data collected to date on how many Australian university students are affected by it. The most relevant study was conducted back in 2006—a survey of Australia’s 97 universities, with 18,773 responses—which revealed widespread experiences of financial hardship. One in eight students indicated that they regularly went without food or other necessities.

Young homeless people who attend university usually take longer to complete their studies, too. The students struggle with what Professor Marty describes as the “legacies of homelessness”—an absence of financial resources, support networks of family and friends, while working in low-paying jobs.

In response to this, the Student Accomodation Services at Sydney University aims to provide some support. “We recognise the devastating impact of homelessness and the impact it has on students’ ability to engage with education,” says Dr Ashvin Parameswaran, head of the Services.

“Many students who reach out to [us] are in between houses and urgently need a place to stay. Student Support Services has designed a number of programs to respond to the needs of our diverse student cohorts, particularly those facing challenges,” he tells Honi.

Students are encouraged to visit the office for direct assistance from the staff, which includes access to emergency rooms for those in urgent need of temporary accomodation, and to the University of Sydney Accommodation Database to assist in locating and navigating off-campus housing in Sydney.

Dr Parameswaran also cites STUCCO as an alternative option, which has “an equitable model whereby students with a reference letter from SRC or SUPRA will be housed temporarily for a period of time at no cost”, and the SRC and SUPRA, who can “assist in referral letters for temporary accommodation”.

* * *

“I’m sure everyone’s experience is different, but for me it was a very rational process of thinking how I was going to survive on a day-to-day basis,” says Danny, 26, who was homeless and living out of his car for a month.

For Danny, it was a matter of looking at the resources available at his disposal, and scoping out all the spots around campus. He found a fridge and microwave in Carslaw to take care of food, and bought a gym membership for toilet and shower facilities. Having a station wagon also meant that he could lie down semi-comfortably. “After that, it was just a matter of finding places to park that wouldn’t attract a lot of attention and wouldn’t get parking fines,” he says.

Living out of his car was “weird” experience, but like many others who find themselves homeless, Danny didn’t have any time to think about anything other than how to survive. At times, he recalls feeling the vulnerability of sleeping on the streets: “There’d be people walking by and you’d hear their conversations, and you don’t know what their intentions are because you’re cut off from them … Or there were nights where it’s just storming really hard, and all you can hear is the wind howling or the rain beating down,” he says.

“You adapt to it—when you’re in that situation, you have to force yourself to do things, and you don’t have the luxury of being lazy or being bored.”

A month later, Danny was accepted for accommodation at STUCCO. “I was just so happy to have a place to come home to every night, and having a key to this place, it was like shelter and security,” he says.

To anyone facing a similar situation, Danny recommends talking to people and approaching the SRC or the University to move away from the silence around youth homelessness.

“It’s really affirming knowing that you can survive those kind of situations,” he says.

* * *

There are broader initiatives in the community attempting to address youth homelessness.

Sydney Council has proposed several projects as part of a wider Strategic Plan to assist people, and is working towards ending long-term homelessness in Sydney by 2017. This is an ambitious aim, and it will almost certainly require the partnership of the government, non-profit organisations, and the corporate sector, with no further cuts being proposed to federal funding.

Other youth homelessness services in Sydney, although limited, are also working. As part of the NSW government’s ‘Going Home Staying Home’ Specialist Homelessness Services, an Inner West Youth Homeless Service is currently in place to support over 450 young people per year. It provides crisis and transitional accomodation, and proactively identifies those who may be at-risk. Other emergency services like Link2home, Temporary Accomodation Line, and Yconnect all work towards providing emergency accomodation and support workers.

However, even these services cannot provide adequate relief to the homeless. A previous Honiarticle found that in 2012, the Homeless Persons Information Centre (HPIC), which caters to approximately 160 people a day seeking urgent accommodation, received 58,664 calls for assistance. Out of this, 45,448 were unable to find anywhere to sleep.

* * *

In Sydney, it seems that the plight of the homeless will not be answered any time soon—reducing youth homelessness is expensive, and the required funding isn’t forthcoming. Nor is it clear who should bear the primary funding burden, the status quo being supported by a convoluted array of federal, state, and local governments.

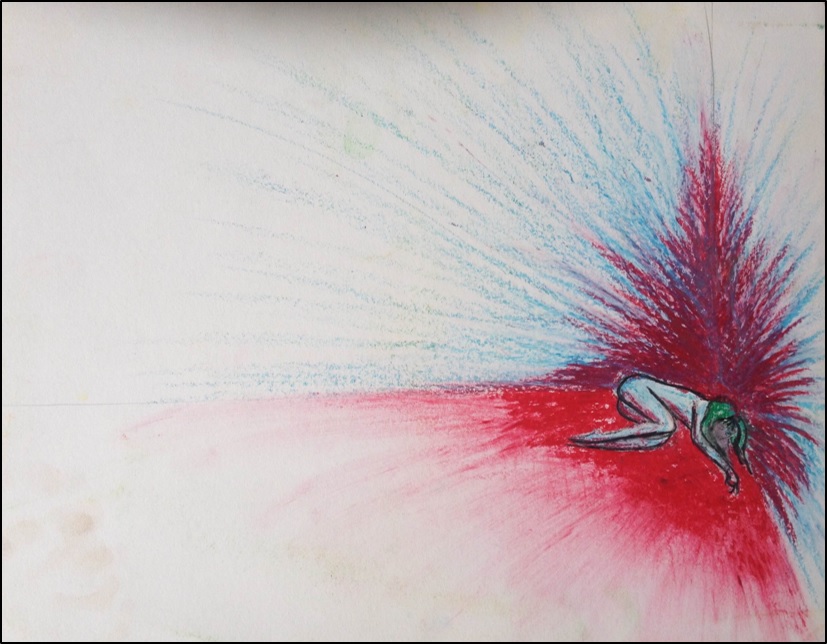

Being homeless is more than just losing a house; it’s losing one’s sense of worth. Those who experience it fast become the most vulnerable and socially excluded members of society. On the streets, they routinely face violence, whether accidental or unintentional, that pervades their sense of being. The violence occurs when people weave through the tunnel at Central Station and kick someone who is homeless along the way. It occurs when a drunk, wealthy person flicks their rubbish at someone sleeping on the pavement on a Saturday night. It occurs when someone calls a beggar asking for loose change a ‘blight on society’.

“They’re not even acknowledging you as a person, you’re the equivalent of a crate,” says Andy. “You don’t own your body anymore, you don’t own anything—you’re not a person, you don’t have capacity to do that. A jacket is probably the only thing you have, and if someone takes it, it’s someone taking your warmth—your world.”

© Honi Soit 2015